Review these 12 peace education frameworks and learn how you can make your own.

by Taylor O’Connor | 27 February 2021

“The ultimate goal of peace education is the formation of responsible, committed, and caring citizens who have integrated the values into everyday life and acquired the skills to advocate for them.” — Betty Reardon

So I made this peace-learning framework once. No, not the one in the image above. That’s the second proper one I made. Similar concept, but entirely different purpose and intended use.

Peace-learning frameworks are seriously critical for any peace education program you want to set up or for any education-type program associated with peace, human rights, anti-racism, social justice, or anything of the sort. I’ve used them tons, and it’s been great, but all too often, such frameworks are misused and misunderstood. And when that happens, well, it’s just a bit of a waste of everybody’s time to be honest.

Let me explain.

My first peace education framework

So I was part of this team that made a peace-learning framework intended to be used in programs all over the world. This was maybe six years ago or so. They actually had a first draft of the thing that was the product of a huge participatory process involving ‘experts’ and practitioners all over the world and stuff. It was great content-wise but needed a bit of refining. So BAM! A little reorganization here, some adjustments there, and we did it! We updated the thing, and it was looking all shiny and nice. More details below. See the Peacebuilding Competency Framework.

Anyways, it was some years later, on an unrelated contract, where I realized how confused people could be with what a peace-learning framework is and how it can be used.

I was traveling to conduct a program evaluation. When I got there (not telling you where… haha), the program team handed me a pack of program materials with an image of this framework printed on the cover. I soon came to see, however, that the program activities and generally no part of the program whatsoever had any relevance to the framework. The team, along with a wide array of very competent partners and people involved in the program, didn’t really know what to do with the thing. And nobody could explain why it was on there or how it was used, other than that it looked cool on the program materials pack and probably sounded cool when they told people about it.

Towards proper use of peace-learning frameworks

This predicament is all too common, unfortunately. The example I used could have been anybody really. I encounter similar situations all the time. People set up education programs for peace all the time that are a bit off the mark. The intention is there, but just bringing people together to talk about peace, maybe draw some pictures of peace, and do some random feel-good activities is not really accomplishing much.

You need a framework. It needs to be the right one for your purpose. And you need to know how to use it. Just grabbing a random framework that looks cool and showing it to people doesn’t cut it. I’ll admit, it took me some time to figure this out myself, and this is part of what I do for a living. Some of the earlier peace education programs I setup could have been a lot better with just a touch of practical know-how on peace-learning frameworks. I’ve learned a lot over the years and will try to lay it out simply so you can avoid the same mistakes that I and so many others have made.

The most practical approach to gain an understanding of what a peace-learning framework is and how to use one is to review a collection of quality peace-learning frameworks. This way, you can see for yourself the similarities and differences amongst them and the unique uses for each.

But first, a little background info. I’ll keep it brief.

A little background info on the global movement for peace education

So peace education really became an established and well-known approach following the Hague Appeal for Peace Conference in 1999. With over 9,000 participants from over 100 countries, it was the largest recorded peace conference in history, the centennial celebration of the first International Peace Conference of 1899 in the Hague. And from it came the launch of the Global Campaign for Peace Education (GCPE).

There was a lot of momentum for peace education at the time, and the United Nations General Assembly soon thereafter proclaimed the years 2001 to 2010 as the International Decade for a Culture of Peace and Non-Violence for the Children of the World. A key pillar of this was ‘to reinforce a culture of peace through education.’ Naturally, following this global funding mechanisms poured money into peace education programming around the world.

A lot of peace-learning frameworks out there, and subsequently you’ll see reviewed below, were either developed in direct association with the Hague Appeal for Peace Conference or with funding support made available during the Decade for a Culture of Peace. Today, however, that funding has dried up, and with it, a lot of the projects and activities associated with it. The frameworks remain, however, and some new ones have been developed, each with their own purpose and intended use.

A Review of 12 Peace-learning Frameworks

Below is a review of 12 quality peace-learning frameworks. In each review, I provide some background, explain uses of each, and share some reflections.

All frameworks are publicly available, and most of the images come from resources that present them. Most have freely downloadable resources, and I have put the links for whatever is available below. Some, particularly older ones, didn’t have images, so I have taken the components of those and put them into tables so you can see a simple visual.

As you review them, you’ll begin to see how unique they all are, each designed for different purposes and uses. This will help you figure out which is right for you, or if you are so inclined, you may take elements of a few of them to create a unique framework for your own unique purpose. I’ll give a little more guidance for you on this in the conclusion section, together with a brief review of common purposes and uses of different types of frameworks.

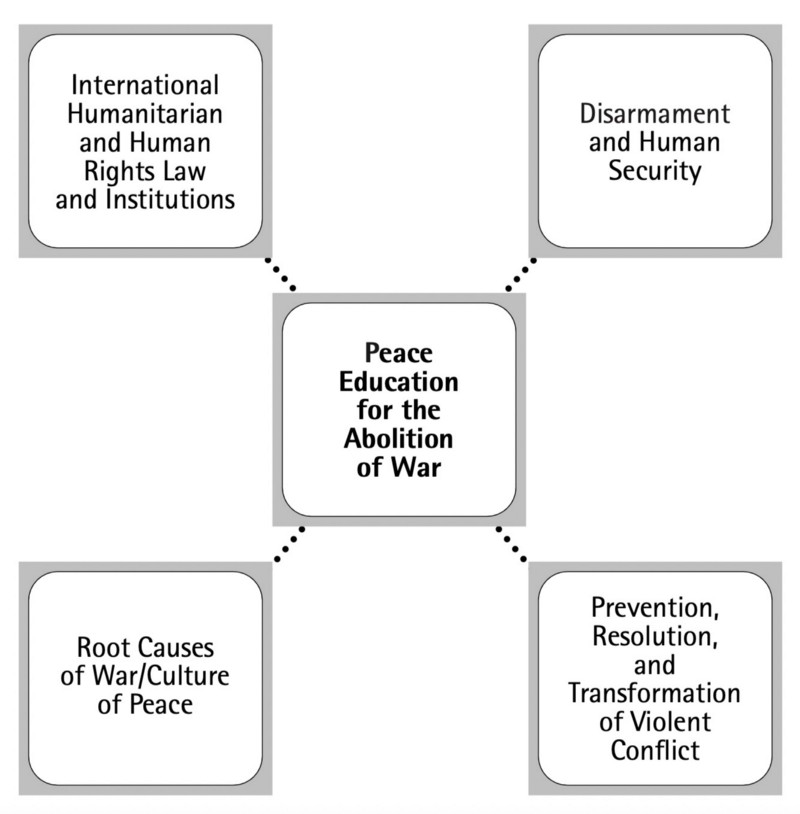

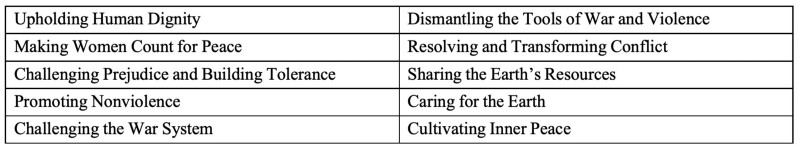

1. Conceptual Framework: Peace Education for the Abolition of War

Background: This conceptual framework is a central component of The Learning To Abolish War manual, produced as a cooperative effort led by the Teacher’s College Peace Education Team under the direction of Dr. Betty A. Reardon and Prof. Alicia Cabezudo at Columbia University. The manual was the first publication of the Global Campaign for Peace Education (GCPE) as part of The Hague Appeal for Peace. The team spent a year reviewing curricula of peace educators from various countries and selecting materials most applicable to the framework.

Framework Overview: This conceptual framework was organized around the core concept of the abolition of war and the overarching goal of achieving a culture of peace, the two central themes that inform the Hague Agenda. The framework is supported by a package of associated lesson plans and companion materials. They were designed for use in the training sessions conducted by the Global Campaign for Peace Education, by teacher educators and classroom teachers of elementary and secondary schools. They were made so teacher educators can adapt the framework and associated educational materials.

Reflection: This one is interesting from the perspective that it was a foundational framework of the GCPE. It is useful for programs that would like to focus on education for the abolition of war. At face value, the framework components seem most relevant to youth and adults; however, if you look into the guidebooks, you will find resources that will help you apply the framework in an age-appropriate way at primary, secondary, and university level.

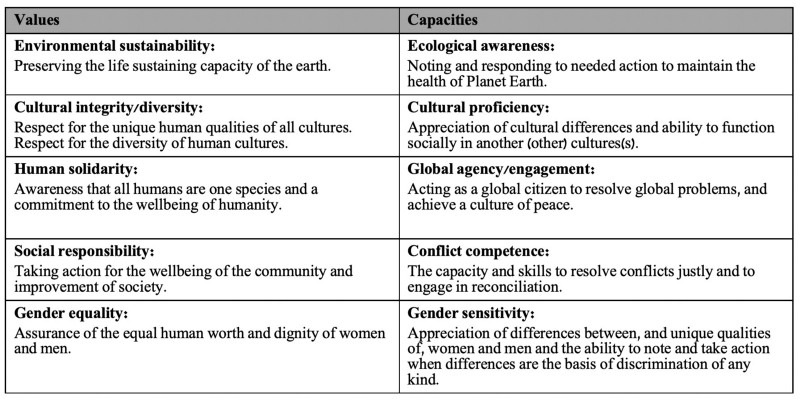

2. Goals for Educating Humane and Responsible Citizens

Background: This framework was developed by Betty Reardon, one of the early pioneers in Peace Studies and Peace Education.

Framework Overview: This framework is built around five core peace values to be cultivated by education for a culture of peace, together with five associated capacities that can be realized through skill development. The values and capacities apply to both individuals and societies. Each of these capacities can serve as a basis for comprehension of cognitive knowledge and can be developed into a range of skills through the various pedagogies that have been devised or adapted by peace education. The original publication that features this framework includes suggested goals and methods.

Reflection: The book where this framework is originally from provides background, rationale, and tools for peace education that are excellent. It also has a great learning matrix that accompanies this main framework. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to find it for free online; however, the Learning to Abolish War resource also provides a lot of support to apply this framework.

This framework is interesting because it was designed explicitly as a holistic framework that applies both to individuals and society at large. Note the title of the framework, Education for Humane and Responsible Citizens. This is an excellent framework to apply to public education systems or some programs with a wide reach.

3. A Holistic Framework for Peace Education

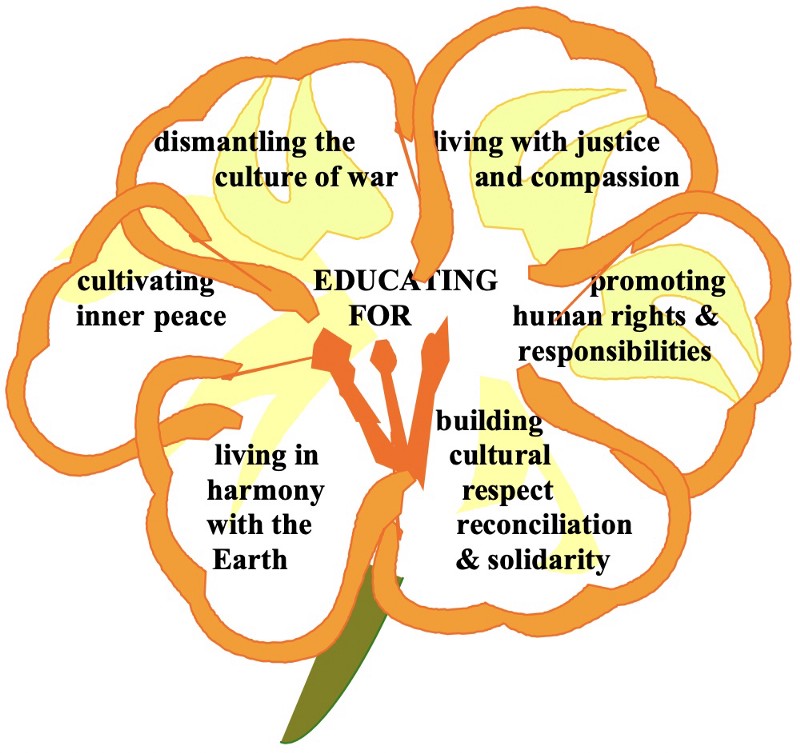

Background: This framework was developed by Toh Swee-Hin, another key figure in the global movement for peace education. Toh Swee-Hinn’s framework takes a holistic, multidimensional approach for peace education to address the complex realities of conflicts and peacelessness facing humanity. Notice how the publication date coincided with the International Decade for a Culture of Peace.

Framework Overview: Each part of this framework is described as a ‘pathway to educating for a culture of peace.’ The themes are represented by the metaphor of a flower to emphasize their interconnectedness as “petals” to form an organic whole.

As a holistic framework, its stated goals for peace education are framed as two interrelated questions: 1) How can education contribute to a critical understanding of the root causes of conflicts, violence, and peacelessness at the personal, interpersonal, community, national, regional and global levels?, and 2) How can education simultaneously cultivate values and attitudes that will encourage individual and social action for building more peaceful selves, families, communities, societies, and ultimately a more peaceful world?

Reflection: This framework was presented in an article and did not have an accompanying resource guide or activities. The article does, however, provide some excellent background and rationale for peace education with a clear description of each component of the framework.

I like the title, Pathways to Building and Educating for a Culture of Peace. ‘Pathways to peace’ is a good way to think about peace education. When you educate for peace, you are opening up pathways to achieve peace. In this framework, each pathway addresses a specific root cause of conflict. The root causes of conflict addressed specifically by these pathways are militarism, structural violence, human rights violations, cultural violence, environmental destruction, and personal peacelessness.

4. Skills for Constructive Living

Background: This is the learning framework developed for the Inter-Agency Peace Education Programme (PEP) implemented jointly by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE). The program was developed starting in 1997 as a response to a conflict situation with refugees in Kenya. It later expanded to Ghana, Timor-Leste, and Sudan, and the program continued for many years. Notice how this program came into being during and throughout the International Decade for a Culture of Peace. Before PEP, there were few peace education materials developed specifically for the African context.

Framework Overview: PEP was designed to enable and encourage people to think constructively about issues, both physical and social, and to develop constructive attitudes towards living together and solving problems that arise in their communities through peaceful means. The program had three strands: 1) the formal education (school) program, 2) the non-formal (community) program, and 3) the training program for teachers and facilitators.

As this was a big program that operated for many years, several resources are available. If you follow the link above, you can access all the program materials, available in English, French, and Arabic. This includes sixteen resources, including teacher guides, training manuals, activity guides, and many other materials.

Reflection: I think this framework was useful for this program’s specific purpose and addressed the issues they had identified associated with the conflict context they operated the first program in. But in my opinion, eighteen elements to the framework is just way too many. It makes things confusing. It is fine to include all these elements, but the framework would be much easier to understand and use if they grouped them.

Also, note that this framework was developed specifically from conflict-affected contexts. So if you’re designing a framework for a conflict-affected context, you may find some of the elements in here useful.

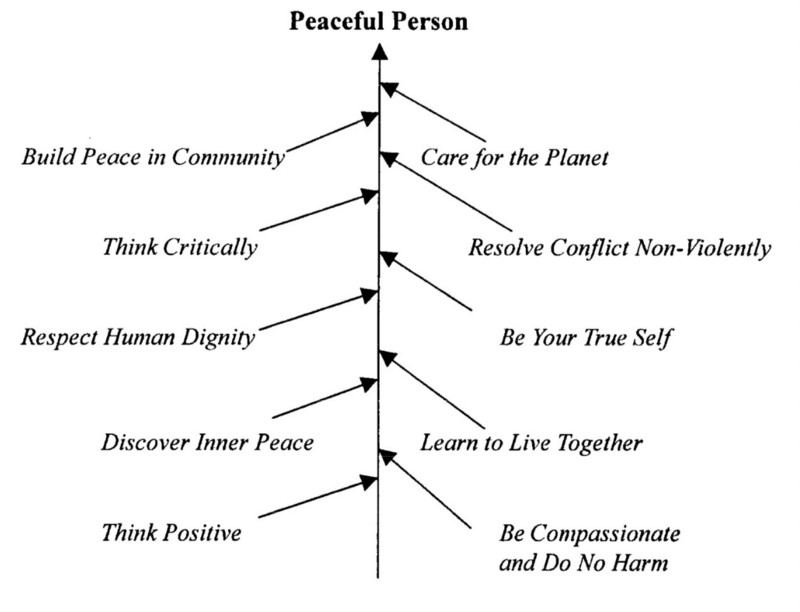

5. Thematic Model of Peace

Background: This framework was developed for the South Asian context. It was a product of a conference on Curriculum Development in Peace Education organized by UNESCO that included educators from India, Pakistan, Bhutan, Maldives, and Sri Lanka. Educators developed the framework and associated teacher guide to support efforts to introduce Peace Education to schools in South Asia. This framework too was developed at the start of the International Decade for a Culture of Peace.

Framework Overview: This framework was designed as a model of peace education for general education. It was developed with the primary objective of helping children grow into peaceful persons. The model consists of ten basic themes that incorporate the fundamental values and characteristics of a peaceful person. The Teacher’s Guide includes learning activities for each of the ten themes.

Reflection: I think this would be an excellent framework for primary-level students. The guide also includes lots of activities under each of these ten framework elements. It was produced for the South Asian context, but I think the framework elements are widely applicable, and also, the activities that come with it can be used or adapted for other contexts.

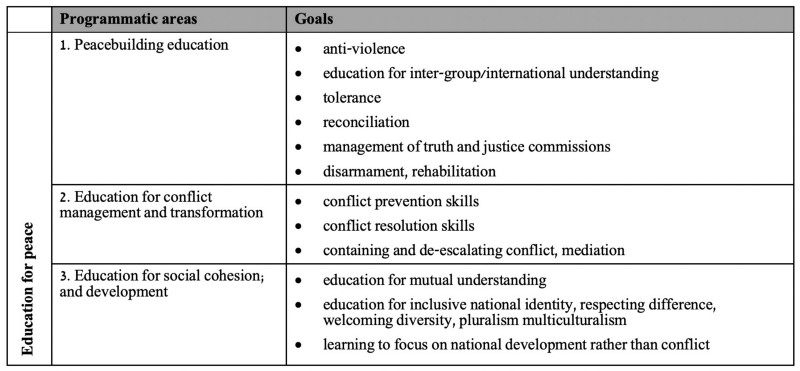

6. Education for Peace Goals

Background: This framework comes from a guide for the design, monitoring, and evaluation of education for life skills, citizenship, peace, and human rights. The guide was a collaboration between UNESCO International Bureau of Education (IBE) and Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ). The purpose of the guide is to strengthen the curriculum dimension known as education for learning to live together (LTLT), which incorporates areas of life skills, citizenship, peace, and human rights. This resource too was developed early on in the International Decade for a Culture of Peace.

Framework Overview: This section presented above maps the programmatic areas and goals of education for peace. The framework in the guide also covered citizenship education and life skills education, but just the peace education section is included here. The framework was not part of a particular program but meant to support others to develop their own programs and curriculum frameworks. So their aim in selecting the programmatic areas and goals was to be as comprehensive as possible in identifying possible goals of each programmatic area.

This framework and associated tools in this guide aim to support curriculum and textbook development, teacher training systems, also national (or project) systems for monitoring and evaluation of schooling. The main focus is formal education, but it could be applied to non-formal programs.

Reflection: This framework and associated tools in the guide can be incredibly useful for designing your own peace education initiatives. I’ve used them myself many times. The guide itself is packed full of guidance and tools for the design, monitoring, and evaluation of peace education initiatives (also for citizenship and life skills).

The guide is very comprehensive and detail-oriented to help you make decisions about what your learning framework should look like and how to put it into action. It can be particularly useful for technical (or other detail-oriented) persons who are taking the lead in designing and implementing peace education programming at a large-scale.

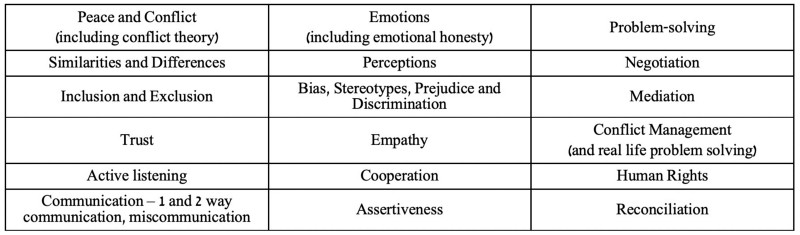

7. Key Peace Education Themes

Background: This framework comes from a comprehensive resource developed by peace education scholars Loreta Navarro-Castro and Jasmin Nario-Galace from the Center for Peace Education at Miriam College in the Philippines. The first edition of this resource was published in 2008. This book is based on the authors’ lifetimes of study, research, and experiences as teachers and trainers.

Framework Overview: The overall goal of the book where this framework is found is to provide educators with the essential knowledge base as well as the skill- and value-orientations associated with educating for a culture of peace. It is primarily directed towards the pre-service and in-service preparation of teachers in formal school systems but may be used in nonformal education. It can also be a resource for those who want to understand peace issues and some of the ways by which they can help work for change towards a more peaceful society.

Reflection: This guide includes lots of descriptions of each peace education theme presented. It is an excellent resource for teachers to get a good understanding of the topics and bring them into the classroom. There are some activities and teaching-learning ideas as well, which are useful. There is also a lot of great stuff on peace education rationale, pedagogy, and teaching methods.

Also, the authors of this book are influential members of the Global Campaign for Peace Education. They have developed an excellent, holistic framework for peace education that can be applied broadly. Their approach to peace education is well-rooted in global best practices for peace education.

8. A Peacebuilder’s Competencies

Background: This framework and associated teacher guide were produced as part of a project called Teacher Training and Development for Peacebuilding in the Horn of Africa and Surrounding Countries. The project’s long-term goal was to develop a critical mass of teachers able to implement effective teaching and learning essential for preparing peace-loving and productive youth in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and Uganda.

Framework Overview: This framework and associated guide were designed to build the capacity of teachers so that they are informed and empowered in why and how to educate for peacebuilding. It offers an analysis of conflict, examines the role of ethics, expands on the elements of transformative pedagogy, and provides practical tools to assess learners’ understanding of peacebuilding concepts and skills. It concludes with 20 engaging activities to support experiential learning.

The accompanying guide includes lots of background on peace education in conflict-affected contexts. It also includes some excellent participatory activities and inputs for the assessment of learning new knowledge and skills.

Reflection: This framework and accompanying guide are excellent on pedagogy and teaching methods. There is a lot on educating teachers to be able to implement peace education effectively. This is very suitable for conflict-affected contexts but can be applied to any context. It was also produced for countries in the Horn of Africa, but the framework is widely applicable. Note that it focuses on competencies for building peace, not just competencies for general peaceful citizens.

9. Five Spheres of Peace

Background: This framework was designed by The National Peace Academy. National Peace Academy describes themselves as a home for peace professionals and community organizers looking to hone their practice and for budding community leaders and changemakers who are seeking knowledge and skills to create safe, healthy and sustainable communities and nurture positive change in themselves, their family, neighborhood, workplace and the world.

Framework Overview: The National Peace Academy describes their framework as five interrelated and interdependent spheres of peace and right relationships that need to be nurtured toward the full development of the peacebuilder. They conduct training programs using this framework to introduce learners to theories and practices to nurture and build peace and engage learners in a reflective inquiry into peace and right relationships. They have also developed some curriculum materials for children and youth using this framework. These are available on their website.

Reflection: This framework is simple and easy to understand. Its simplicity helps those using the framework to apply it effectively. Within each sphere, one could break down more specific skills and knowledge to develop practical learning objectives to integrate into the lesson plans. But as a general overview, I think this framework is nice. It can be applied widely, and depending on the context and learning setting, it can be split up easily. For example, students could take a course that covers ecological topics, one for personal peace, etc., etc. etc.

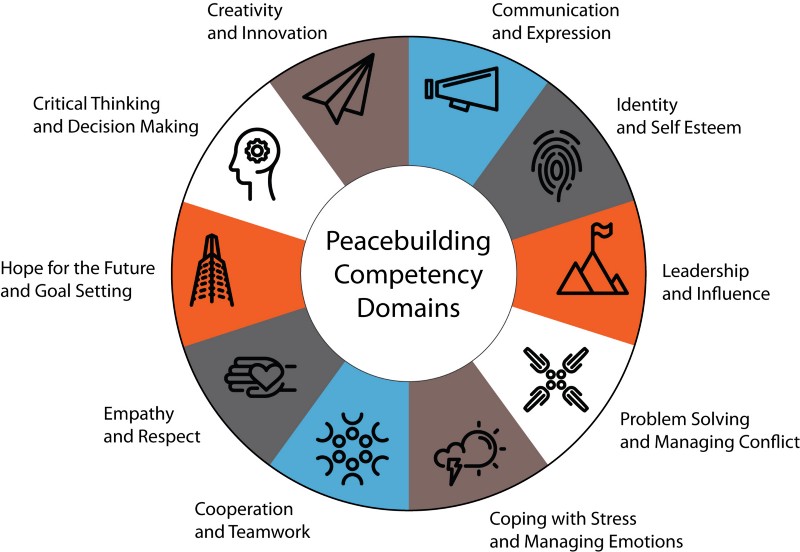

10. The Peacebuilding Competency Framework

Background: This framework was developed by the Adolescent Development and Participation Section (ADAP) at UNICEF. It was based on comprehensive research conducted during UNICEF’s global Peacebuilding, Education, and Advocacy (PBEA) Programme (2012–15) on peacebuilding in conflict-affected contexts. With a team at UNICEF HQ, I was personally involved in developing this framework to the form you see today.

Framework Overview: This framework is specifically designed to support the capacity of adolescents in conflict-affected contexts to build peace. The Adolescents as Peacebuilders Toolkit provides guidance and tools to use this framework to design, monitor, and evaluate programs using this framework. It also provides a comprehensive map of knowledge, attitudes, and skills associated with each competency domain. A companion resource integrated with this framework, The Adolescent Kit for Expression and Innovation, provides a full package of participatory activities and guidance materials for those implementing programs for adolescents in conflict-affected contexts.

Reflection: When developing this framework, I remember thinking that these competencies are important for everyone to learn. We were developing it specifically for adolescents in conflict-affected contexts, but I think it is applicable far beyond this. I like frameworks with a solid ten components (and this is a contributing factor to why this was presented as ten), but I also think that it is useful to have a focus of the program. For longer, comprehensive programs there is a lot of time to work on each of these competencies. For shorter programs it is helpful to have a specific focus.

The Adolescent Kit for Expression and Innovation that uses this framework is used in countries worldwide, in both conflict-affected contexts and those not affected by conflict. It has been used to develop short programs for conflict-affected adolescents, and also the framework has been integrated into public education learning frameworks.

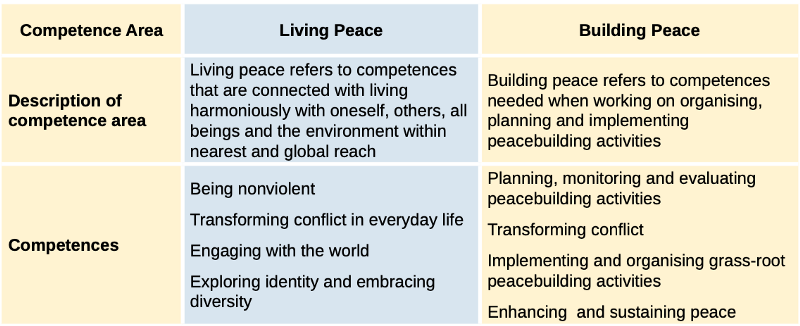

11. Peace Education Competence Framework

Background: This Peace Education Framework was a product of a project for mainstreaming peace education in the European Union. The Framework and associated guide aim to enhance the professionalization of peace education in the youth and non-formal education sectors by providing a tool for planning, monitoring, ,evaluating, and assessing competence development for young people through peace education. The development of the framework was the product of a collaborative process between partner organizations in Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands, Turkey, and the United Kingdom, involving over a dozen contributors.

Framework Overview: While the Framework was developed for educators in non-formal learning, it can also be used in formal settings or organizations to develop trainer teams and capacity-building. Additionally, while the framework was designed to support youth groups and activities, it can be used with all age groups and all educational contexts, including adult, vocational and higher education. The accompanying guide outlines details of peace education competencies, together with learning objectives and learning outcomes.

The framework is divided into two separate frameworks for two unique groups: living peace and building peace. Living peace refers to competencies connected with living harmoniously with oneself, other living beings, and the environment both locally and globally. Building peace refers to competencies needed when working on organizing, planning, and implementing peacebuilding activities.

Reflection: I think this framework is interesting because it is two frameworks, one for the general public and the other for peacebuilders, though peacebuilders themselves may benefit from both. They have been thoughtful about what competencies are needed for the general public to promote peace in society and what competencies are specifically needed for people to build peace effectively.

One thing that is implicit here, however, is that the ‘peacebuilders’ they refer to are people how to work as peacebuilders within the international aid industry. Notice how one competency associated with ‘building peace’ is on planning, monitoring, and evaluating peacebuilding activities. The implicit part is that these are activities conducted within the context of the international aid industry.

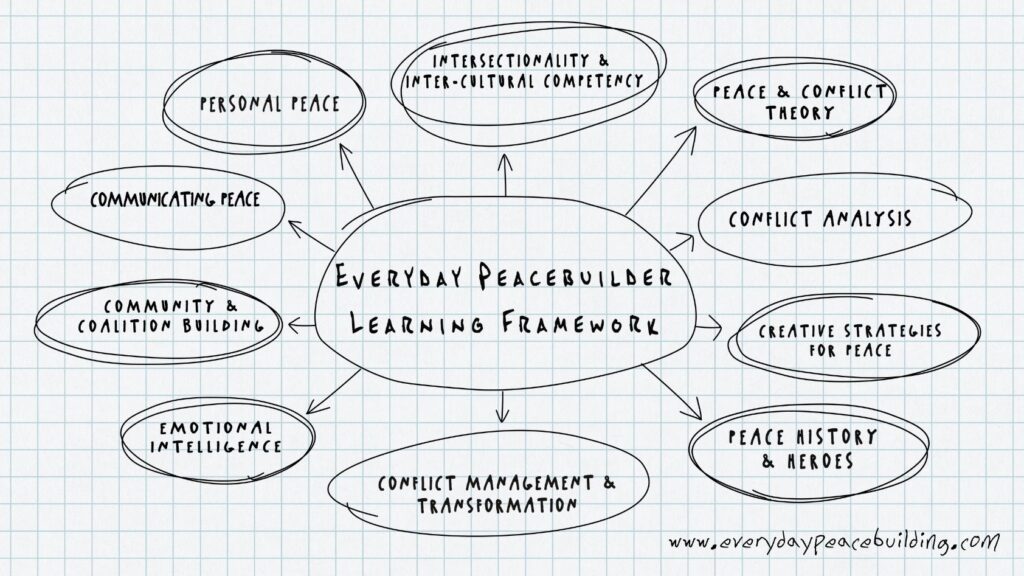

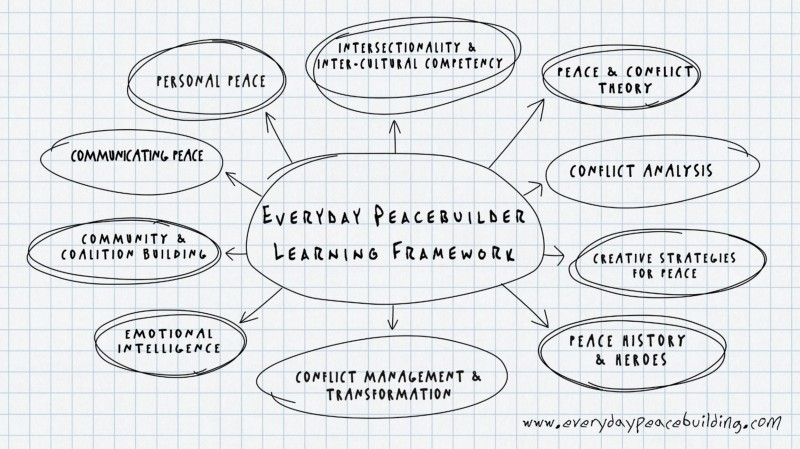

12. Everyday Peacebuilder Learning Framework

Background: I started blogging last year to teach people how to build peace, and I’ve been growing a community of peacebuilders around the world who are building peace in a wide variety of ways. As the community has grown, I’ve been engaging in discussions with people about common challenges they face in building peace. And after analyzing a considerable amount of feedback on this, I developed a collection of learning themes that will help peacebuilders to overcome common challenges they face in building peace and generally to build peace more effectively. I’ve used this to begin to develop learning materials to support peacebuilders of all kinds.

Framework Overview: The purpose of this learning framework is to make you a more effective peacebuilder. You don’t need to know all of these things or even be strong in all of these. Learning in these areas will strengthen your capacity for building peace, ultimately helping you be able to transform issues you care about and make peace a reality. All segments are interrelated.

Emotional intelligence: Peacebuilders must be strong in emotional intelligence. They must be able to understand their emotions and the emotions of others. They must be able to calm themselves in tense situations and to engage effectively with challenging persons.

Intersectionality & inter-cultural competency: These go together because, for peacebuilders, it isn’t simply about getting along with diverse persons. It is deeper than that. Developing a practical understanding of intersectionality means that a peacebuilder must recognize different types of discrimination and privilege experienced by people (oneself included) due to the interaction of various elements of their identity like gender, race, class, sexuality, religion, disability, etc. A peacebuilder will apply this understanding in engagement with diverse persons and the issues that affect them when working for peace and justice.

Peace & conflict theory: This section covers the fundamentals of peace and conflict theory, which will help you be a more effective peacebuilder. It includes learning about structural and cultural violence, human rights, militarism, conflict dynamics, social justice issues, etc.

Conflict analysis: This is where you apply the peace and conflict theory. Conflicts are complex, and we must develop our capacity to analyze conflict, understanding different dimensions of conflict and their roots. This is the foundation for developing effective strategies to build peace.

Creative strategies for peace: Creativity is a necessary component of making progress towards peace. Beyond that, learning about a wide array of creative approaches will expand your ability to come up with innovative ideas for how to build peace. Additionally, learning about strategic peacebuilding will enhance the effectiveness of your efforts. Creativity is an essential component of strategic peacebuilding.

Community & coalition building: Building a community of like-minded peacebuilders can strengthen your own ability to build peace. Building a coalition amplifies impact. These are both actions, but they require particular skills that can be developed.

Communicating peace: Many peacebuilders struggle to communicate their message of peace. Their peacebuilding efforts are not accepted by their families or communities. People involved in conflict or in influential positions are not interested in peace and do not want to hear their message. People think peace is not realistic. They believe in myths about the necessity of war. They are not interested in listening about social issues or issues of injustice. Developing your ability to communicate peace is a key, though often neglected, skill that can be developed. Practical applications of this skill in formal and informal ways are numerous.

Conflict management & transformation: If you are a peacebuilder, it is likely that at one point or another, you will be in a situation where you have to manage an active conflict situation and help people involved come to a suitable resolution. These skills can be learned. Additionally, you can learn techniques to transform conflict at the root. These are techniques that can be learned and then developed with practice.

Peace history & heroes: Understanding peace history, key events, and those peace heroes associated with historic peace movements, you will find lessons you can apply to build peace today. Also, communicating to others about peace history and heroes can have a powerful effect on transforming conflict in the present day and showing people that peace is possible. You can learn about peace history and heroes from around the world and your local context.

Personal peace: Cultivating personal peace will enhance your ability to build peace with others and the world around you. It is common that peacebuilders work hard and are driven by their passions. They don’t care for their wellbeing, and they get burnt out. Developing personal peace is a critical yet often forgotten component of building peace.

Reflection: This is a framework for peacebuilders and people who are passionate about doing their part to build a more peaceful and just world. It is not for the general public. A peacebuilder does not need to be convinced about the humanity of others and does not need to gain awareness about injustices experienced by others. They may deepen their knowledge in related areas; however, it should be assumed that a peacebuilder already has a certain level of awareness and is passionate about transforming social issues that bring about injustice and human suffering.

This is a framework designed for people of all kinds who already have the awareness needed and high motivation to build peace, and it focuses on key skill areas that will help them in their efforts.

To use a framework or make your own?

As you review the frameworks above, you should observe that there are two major distinctions amongst them. Some are for the general public, and others are for peacebuilders specifically. There is a major difference between setting up a peace education program for the general public (i.e., integrated into the formal school systems or generally rolled out to reach as many people as possible) and learning programs specifically for persons seeking to build peace.

So if you’re planning your own program, first you’ll need to make that distinction.

Additionally, you’ll see that each framework is designed for a different context and focus. Some are for children, others are for youth, and some are for adults. Some are for persons in situations affected by violent conflict or displaced persons. Some are designed for a more broad application, while others are developed for specific countries, cultures, or contexts. Some are designed specifically for school systems, others for non-formal education programs or out-of-school youth, and others for specifically targeted training programs.

And finally, each covers different themes, often targeted for specific learning outcomes associated with human rights, environment, gender, multi-culturalism, disarmament, or otherwise. Not all programs should expect to cover all themes.

You’ll have to figure out what the purpose of your program is; what you’re trying to achieve with it. Then be clear on who the program is for. When you know this, you can start to imagine some specific learning outcomes that you may have associated with the program. And elements of your framework should be associated with specific learning outcomes that contribute to a more long-term outcome you are hoping to see.

Adapting frameworks and designing peace education programs

Then you have a key choice to make: you can use any of these frameworks as they are presented, adapt them to your needs, or create your own framework. I always recommend that people make their own because making your own framework ensures that you (and possibly your team) put in the intention needed in designing a program that is relevant to your context.

And once you do that, the curriculum or sequence of activities included in the program must be associated with the themes of your framework. If the program is more formalized, you may consider teacher training on these elements and develop other teacher/facilitator support materials and possibly program admin or coordination guidance materials associated with the framework.

Prepare a more detailed and step-by-step process for this in a blog post at a later date, and it can be used as a companion article to this blog post, but until that time, I hope this is helpful for you.

Further resources

If you like this article, be sure to check out our article 100+ Free Education for Peace (and Justice) Resources Online. Or discover other resources on the Resource Page of Everyday Peacebuilding.

Be sure to subscribe to our email list by clicking HERE. I send out a weekly list of all the best resources coming out from a broad range of global efforts to build peace.