Discover these unsung racial justice heroes and the lessons we can learn from them.

by Taylor O’Connor | 1 September 2020

“It is the curse of minorities in this power-worshipping world that either from fear or from an uncertain policy of expedience they distrust their own standards and hesitate to give voice to their deeper convictions, submitting supinely to estimates and characterizations of themselves as handed down by a not unprejudiced dominant majority.” — Anna Julia Cooper (A Voice from the South, 1892)

It was a typical day, early spring in Memphis, when a mob dragged Thomas Moss and two other men from their jail cell and put them to a slow, painful death much to the entertainment of the crowd that had gathered.

Moss and his friends owned The People’s Grocery, a shop in a black neighborhood just outside of Memphis city limits. Their initial troubles with the law stemmed from the success of their grocery store. And the white-owned grocery store just across the street that had until then enjoyed a monopoly on the local market would not stand for it. That they were unlawfully jailed was not enough. The mob mobilized white rage to put an end not only to their rival grocer, but also to its black owner.

It was 1892, fifteen years after the end of the Reconstruction Era, and the whites in Memphis, as anywhere in the South, would employ all means of violence to stifle the ability of blacks to gain any measure of economic prosperity or political representation. In a reign of terror to uphold white supremacy, over 2,000 black Americans were lynched in the 14 years of the Reconstruction era alone, and thousands more to this day. Lynchings carried out with the complicity of authorities were commonplace, but were then given little attention.

But Moss was a close friend of Ida B. Wells. Wells was the godmother of his child and the co-owner of a local black newspaper. She frequently wrote about race issues in Memphis and elsewhere. Wells was out of town when the incident occurred, but the brutal murder of her friend would motivate her to take up what would be a life-long crusade to end the practice of lynching in the United States. The legacy of her crusade continues to this day as federal anti-lynching legislation has time and again been blocked by conservative politicians for over 100 years.

Unsung racial justice heroes

There are a few racial justice heroes we hear a lot about, some that those interested in the topic know, and still so many more that we overlook, yet their contributions are no less profound.

I want to take a closer look at a few of the lesser-known, less celebrated heroes for racial justice that inspire me, and from whom I think we have so much to learn that we can apply in today’s fight for racial justice. Initially, I had a much longer list, however, the lives and achievements of each are just too great that brief excerpts don’t do them justice. So while I’ll cover others in later posts, let’s look closely at the lives, achievements, and lessons we can learn from 3 superheroes for racial justice.

Here we have Ida B. Wells, Anna Julia Cooper, and Marielle Franco. You may notice that all three are women. Most of the names on my long list of unsung heroes are women as it is the contributions of women that we too often overlook. Even if you may know any of these, there is often much about them and their contributions that gets overlooked.

1. Ida B. Wells: a pioneer in racial justice

Ida B. Wells (16 July 1862–25 March 1931) was an African American journalist and feminist in the era of women’s suffrage who campaigned to expose and end the practice of lynching in the United States in the 1890s. She was a pioneer of investigative journalism and used the power of the pen to force the nation to confront the horrors of lynching. She organized peaceful protests and boycotts, and advocated for federal protection of blacks in the United States. At barely 5 feet tall, she was fierce and uncompromising in her ideals.

In response to the murder of her friend Thomas Moss, she penned an article to the black community of Memphis. In it she stated, “There is, therefore, only one thing left to do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.” At 30 years old, Wells organized boycotts of white-owned businesses and made plans for over 6,000 people to leave Memphis. She would later describe this experience as her “first lesson in White Supremacy.”

From there, she went up North and connected with black women’s groups. She told them about lynching in the South, and from the women collected 500 dollars to support her to research and publish her findings on lynching. Wells gathered facts and statistics and stories about lynching. She used white-owned newspapers to verify her information so that the white community couldn’t deny her accusations. She highlighted a sudden increase in lynching of black Americans since slavery was abolished, as individual black bodies no longer held economic value to whites. In her writing she named the victims of racist violence, and she told their stories.

She found that the rape of white women was often the reason cited to lynch black men, but that rape allegations were most often an “excuse to get rid of Negros who were acquiring wealth and property.” She documented how most relationships between black men and white women were known as consensual and charged that “defense of white women’s honor allowed white men to get away with murder by projecting their dark history of sexual violence onto black men.” By exposing the truth of lynching and shining a light on the historic rape of black women by white men, Wells challenged stereotypes created by white men that black men are rapists and criminals, and that black women are temptresses.

Understanding how critical the English market was to Southern cotton, Wells traveled twice to England to garner support for her campaign and to sway the British public to boycott cotton from the American South. She coordinated with suffragist leaders, she met politicians and royalty, and she delivered moving speeches in front of large audiences. The shock and outrage about lynching that she generated from the British public shamed Southern whites for their brutal and ruthless treatment of African Americans.

For Ida’s relentless advocacy, lynching quickly emerged as a topic of national debate, and lynching took a sharp decline just two years after Moss’s murder. Memphis itself wouldn’t see another lynching for twenty years.

Wells was also active in the suffragist movement and black liberation activism, and she never compromised her ideals. She gained developed close friendships with (white) suffragist leaders, all the while being vocally critical of the movement for ignoring lynching and excluding black voices. She played an instrumental role in the formation of the National Association of Colored People (NAACP), but was edged out of leadership by those who took a more accommodating stance to gain support from the white establishment. In 1918, Wells was selected to be a delegate to the peace conference at Versailles that followed World War I, but was denied a passport and thus couldn’t attend as she was considered “a known race agitator” by the U.S. government.

There are many people who have accomplished great things in this world, but it is those so fiercely independent who push through against all odds as Wells did for whom I reserve my deepest respect and admiration. Wells died in 1931 at the age of 68 of kidney failure before able to finish her autobiography.

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.” — Ida B. Wells

Lessons we can learn from Ida B. Wells:

Lesson 1: As Wells was, be ruthless and never compromise your ideals. Your ideas may be ahead of their time. The only way to make them a reality is to keep pushing through.

Lesson 2: Attack the foundations of white supremacist ideology, all too commonly held, that influence harmful perceptions of persons of color and produce violent outcomes. Do this, as Wells said, by “turning the light of truth upon them.”

Lesson 3: Wells used the shock and outrage about lynching that she generated from the British public to shame Southern whites. Never underestimate the power of shame. Shame those who perpetuate systemic racism and the violence it produces, who dehumanize and criminalize black people, who distort public perception, and who stoke (white) nationalism. Shame them mercilessly.

2. Anna Julia Cooper: a thought leader in racial justice

Anna Julia Cooper (10 August 1858–27 February 1964) was an American writer, educator, and activist who fought for the rights of African Americans, women, the poor, and all marginalized people. Born into slavery, Cooper’s formative years spanned the Civil War and Reconstruction, and she was active during the era of women’s suffrage, Jim Crow and segregation, all the way to the renewal of the Civil Rights movement. Sometimes referred to as the mother of black feminism, Cooper’s writing informed the thought of her more celebrated male contemporaries, W. E. B Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, and her ideas continue to influence feminist thought and social theories to this day.

Her book A Voice from the South, published in 1892, challenged the commonly held belief that blacks were naturally inferior to whites, highlighting the hypocrisy of America’s founding fathers’ declaration that “all men are created equal” whilst holding slaves themselves. Cooper chronicled the atrocities of slavery, exposing white slave owners as a rapists, who fathered children by female slaves, exploited them for their labor, and profited from their sale. This is a recurring theme in her writing not only because it was a common practice of slavery, but also because it was her own her lived experience born of a slave mother raped by her slave master. She highlighted the racialization of gender and the sexualization of race and exposed racism embedded in religious and political institutions, schools, health care, and other institutions.

She emphasized the connectedness of women suffrage, racial justice, and class conflict, and outlined the need to eliminate all interconnecting systems of oppression. She believed that the only way feminist goals can truly be achieved is when all oppressed people work together. Cooper’s book gained national attention, and Cooper began speaking at events across the U.S. and beyond. She spoke about the needs of African American women at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, and at the first Pan-African Conference in London in 1900.

She was a vocal critic of the women’s suffrage movement and its leaders for their deliberative exclusion of non-white voices, and was equally critical of black male leaders for overlooking the contributions of black women. She advocated for a bottom-up approach to leadership in the social movements of the day and stipulated that community action at the local level can have an impact at the national level. She advocated that black women must become agents of their own future and that educated black women were necessary for uplifting the entire African American community.

At the same time, Cooper, with other black women across the nation, began to create clubs and associations to promote the well-being of marginalized African American communities. She co-founded the Colored Woman’s League in Washington D.C. in 1894 and was active in the wider Negro Women’s Club Movement. She converted her home into an intellectual and community hub and was an active member of D.C.’s Colored Settlement House (akin to Jane Addams’ Hull House in Chicago). Through these spaces, she worked to address a range of issues relevant to the needs of the working poor around her, including education, housing, and unemployment. The settlement house ran classes, clubs, recreation activities, and started neighborhood improvement initiatives.

Education and social justice for her always went hand in hand. Her philosophy of social justice informed her philosophy of education, and her philosophy of education informed her social justice work. Though few learn of Anna Julia Cooper, we are all better for her contributions to tearing down all forms of oppression and for the profound influence she did indeed have on so many who came after her. Her legacy lives on.

“Let woman’s claim be as broad in the concrete as in the abstract. We take our stand on the solidarity of humanity, the oneness of life, and the unnaturalness and injustice of all special favoritism, whether of sex, race, country, or condition. If one link of the chain is broken, the chain is broken.” — Anna Julia Cooper

Lessons we can learn from Anna Julia Cooper:

Lesson 1: Those who knew Cooper at the time have written of her ‘frugality’ and simple life. She was, as we would term today, a minimalist. And I believe that her simple lifestyle was key to her wisdom and ability to be involved in so many social justice activities. Living a simple life can help you focus time and energy on your passion for justice, gain clarity of mind, and advance your cause.

Lesson 2: Cooper advocated for and employed a bottom-up approach. Grassroots activism can and does have a national, even global impact. Focus on what is in front of you. Ripples turn to waves.

Lesson 3: For Cooper, it was necessary to take action to eliminate all interconnecting systems of oppression, a concept that would later be termed as ‘intersectionality.’ She drew parallels in struggles for black liberation across continents, and built alliances globally. The struggle for black liberation is global in scope and interwoven with the struggles of others. The movement is stronger when coalitions are formed with other oppressed groups in your country and globally.

3. Marielle Franco: a modern racial justice hero

Marielle Franco (born 27 July 1979–14 March 2018) was a Brazilian feminist, activist, and campaigner against police violence who got involved in politics as a means to make change. Those she knew well describe her as a brave and animated fighter. She was simultaneously a voice for the poor, for Afro-Brazilian women, and for the LGBTQ+ community, all of which formed her own identity.

Growing up in Complexo da Maré, one of the largest favelas (slums) of Rio de Janeiro, Marielle understood the relationship between poverty, racism, and violence well. She lived it. Favelas like Maré were ‘ground zero’ for Brazil’s war on drugs. And while basic services like schools, hospitals, and even sanitation are severely lacking in favelas, infamously corrupt and abusive security forces regularly patrol the streets.

Marielle rose up as a vocal critic of police brutality targeting communities of color in 2005, after a ‘stray bullet’ from a shootout between police and drug gangs killed her longtime friend. She fiercely denounced violence and extrajudicial killings carried out by security forces. She would organize public events to discuss issues like police brutality, sexual violence, and LGBTQ+ rights. And it was through speaking out against state violence that Marielle launched herself into Brazil’s political scene.

Advocating for the representation of diverse voices in Brazil’s political scene, she was voted to be a City Councilor and moved quickly to effect legislative changes in the issues she cared about. In a country where more than half the population is black or mixed-race and where wealthy white men dominate political decision-making, her representation as the only black woman in Rio’s 51 member City Council was hugely significant. On the City Council, she would be a sole voice for the rights of the poor in the favelas, of the LGBTQ+ community, and of the black community.

As City Councilor, she chaired the Women’s Defense Commission and pushed to get city bus routes redirected so women could get off at brighter, safer spaces at night. And with the Rio de Janeiro Lesbian Front, she proposed a bill to create a day of lesbian visibility in Rio de Janeiro. When the President signed a decree ordering the military to intervene in the ongoing violence in Rio, Marielle got herself at the head of a commission that would monitor potential abuses associated with the intervention. Having lived through previous military interventions, she was well aware of how extrajudicial killings and disappearances so common during military interventions like this only exacerbated problems in the favelas.

But just 18 months into her term as City Councilor, and before she could carry out her duties at the head of this commission, Marielle Franco was gunned down in cold blood. She was in her car on her way home from speaking at an event called Black Women Changing Power Structures. A few days before her murder, she denounced the killing of two young men from a poor neighborhood in Rio’s North Zone, and with it a stern indictment of the Military Police battalion responsible, long known for their corruption and lawlessness. Brazilian media reported that the bullets that killed her were part of a batch sold to federal police in 2006. The windows on her car were tinted. The assassins knew where she was sitting. It was calculated. They say her murder was carried out by professionals.

In the days following her death, the rhythm of life in Brazil was disrupted. People flooded the streets. And amidst a fury of tears and of rage, masses of people demonstrated their love for everything Marielle stood for. They chanted her name. And they marched to the corridors of power shouting, “Marielle presente! (Marielle is here!)”

“How many more must die for this war to end?” — Marielle Franco (on Twitter, one day before her death. In reference to the ‘war on drugs’, a war against the poor and against blacks.)

Lessons we can learn from Marielle Franco:

Lesson 1: Marielle’s life and legacy remind us of the global scope of the struggle for black liberation. The movements may take different forms, but patterns of oppression are constant.

Lesson 2: Tangible, structural change can be made in the halls of governance. Representation in government is important. Voting is critical. That’s why those in power were so fearful of Marielle’s presence on Rio’s city council.

Lesson 3: Those who benefit from unjust social structures will employ any means of violence, both sanctioned state violence or extrajudicial violence, to stamp out those who stand to make real, systemic change. Be vigilant!

Applying what we learn from these unsung racial justice heroes

When we develop our knowledge about racial justice heroes like these, our efforts for justice today are strengthened. It serves those who benefit from the ideology of white supremacy and systems that carry out its legacy that we know very little about our heroes for racial justice past and present. Learning about racial justice heroes from the past like Ida B. Wells and Anna Julia Cooper can give you pride and strengthen your resolve. Exposure to heroes in other parts of the world like Marielle Franco connects us to the struggles for racial justice worldwide, and unity brings strength.

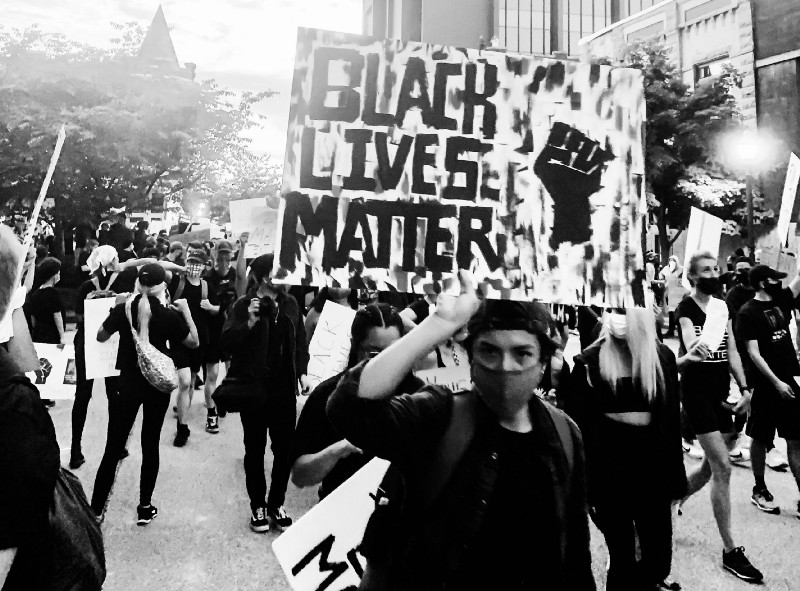

And the lessons we learn from them can be applied by anyone to make a contribution towards racial justice, however small. I find that people get hung up on protests, and don’t get me wrong, protests are useful and necessary. But don’t go on thinking that protests are the only way to make change, because with this thinking, if organizing protests isn’t your skillset, then you will go on to believe that you have nothing to contribute to the cause. This is a major loss. Everyone has something to contribute.

Wells exposed hidden truths, campaigned, boycotted, and built coalitions. Cooper created new ideas that influence liberation struggles to this day, and she set up community centers to care for the needs of all oppressed persons. Marielle educated her community and got into local politics. For me, I’m not a public speaker like Wells. Politics isn’t for me like it was for Marielle. I don’t have community ties, as did Cooper. My contribution, however small, is in writing and education. Learning about the lives of these heroes, reading the books by Wells and Cooper, and articles on Marielle’s life have helped me immensely in how I approach my writing and peace/justice education work.

In these stories, I hope that you find some inspiration that will help you find your own unique way to contribute to the struggle for racial justice and other related struggles of all oppressed people. And keep educating yourself. There is a lot more information available on these three heroes, and there are so many more peace and justice heroes out there from whom you can learn.

For further resources be sure to sign up for our newsletter (the best peacebuilding newsletter out there!) to get connected with all the best articles, videos, podcast episodes, events, downloads, learning opportunities, and other resources on building peace published each week, selected from a broad array of global efforts to build peace. Subscribe by clicking HERE.

And if you found this article helpful and want to find more blog posts like this mapping organizations that build peace across a wide array of themes be sure to check out our Resources page!